|

That's odd with the link. Sorry guys, here's the article:

Why can’t fantasy authors escape from Tolkien’s shadow?

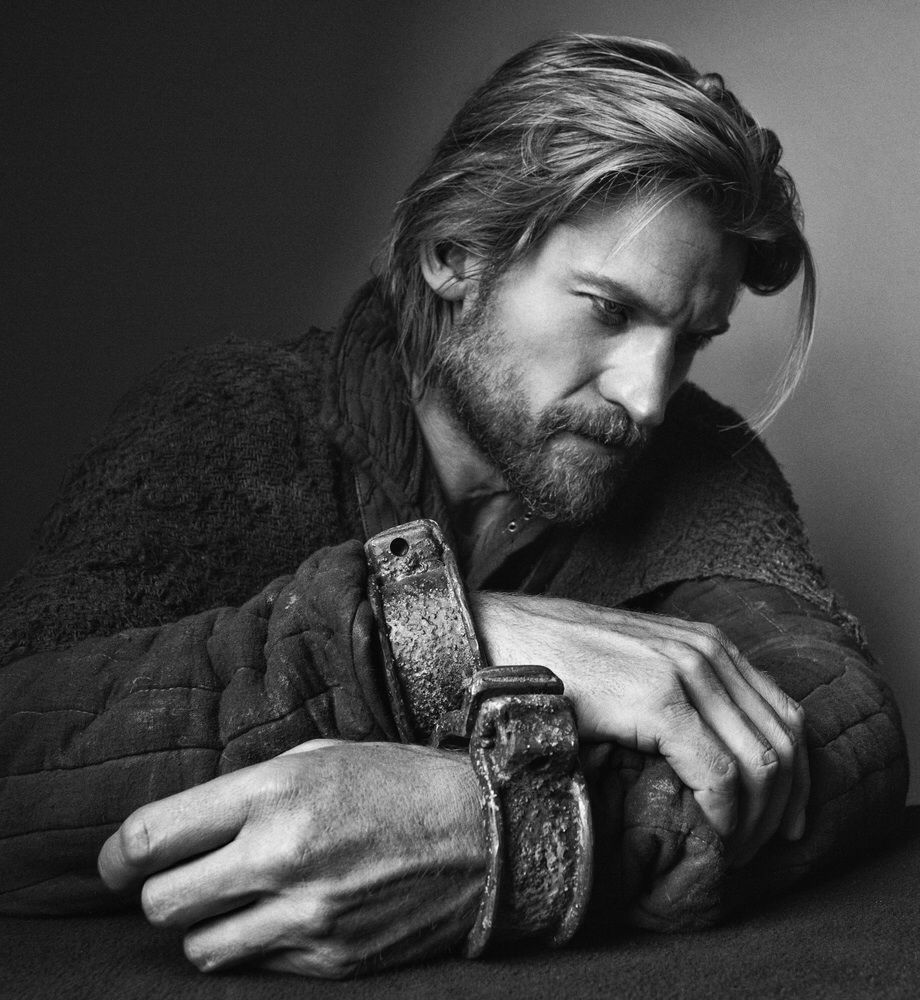

That question is more relevant than ever as Game of Thrones concludes its fourth season on US TV, becoming the highest-rated series ever for broadcaster HBO. More than 18.4 million viewers have tuned in each week this year. The series, which features the epic battle for the throne of the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros, has driven readers back to George RR Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series (five books so far, with another two or three promised), just as Peter Jackson’s films brought a new audience to JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

In early June Martin promised to name a character after anyone who donated $20,000 to a wolf sanctuary. A linguist is now developing language lessons, based on the tongue of one of Westeros’ fictional cultures. And Northern Ireland, where the series is filmed, is benefiting from tourism in the same way New Zealand did from The Lord of the Rings.

It reminds me of a time 40 years ago, when you could find slogans like “Frodo lives!” scrawled on the walls of the New York City subway. In the 1970s, the idea of Middle Earth and the hobbits’ Shire, with its greenery, feasting and furious smoking, chimed with the counterculture. Tolkien’s fantasy, written in the 1930s, as World War II loomed, flourished in popularity as a “green alternative to each day’s madness here in a poisoned world,” as the novelist Peter Beagle put it in 1973.

Now once again, we are enthralled by tales of kings and queens, ladies and knights, wizards and dragons, elves and giants, animated trees and zombie warriors. Once again, we are immersed in battles and court intrigue as kingdoms vie for power. Once again, a unifying enemy looms in the distance. For Tolkien, evil crept in from the East; for Martin, the danger is in the frozen North, beyond the 700-ft wall erected 8,000 years ago to keep out an invasion by the White Walkers, essentially a horde of zombies.

Creators of worlds

Tolkien’s central hero is an Everyman – a humble hobbit, of an ancient people noted for loving “peace and quiet and good tilled earth”. Martin hones in on the royals, targets for other crowned heads in the Seven Kingdoms, as well as their own family members. And when a king is beheaded, woe be upon the land.

Granted, Martin’s A Song of Fire and Ice novels are tonally different from Tolkien. On behalf of Elven-kings, Dwarf-lords, and mortal men, Tolkien’s sunny hobbit Frodo Baggins takes on the burden of keeping the “Master-ring, the One Ring to rule them all” from the Sauron the Great, Dark Lord in the Land of Mordor who would rule over all. Frodo is even capable of partially resisting the power of the Ring in ways humans cannot. Tolkien’s tone in The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings novels, can even be romantic, as Elven maidens fall in love with human men and give up their birthright of immortality.

Martin’s darker, grittier fantasy claims the medieval turf of blood and gore, infanticide and incest. The great dynastic houses are weakened, and petty fights for the throne undermine the need for a united defence against the looming enemy beyond the Wall. He emphasises the worst in his characters, gives even the most ethical humans impossible choices, and kills them off capriciously. In Martin’s world, ruthlessness wins.

But the basics in The Lord of the Rings and A Song of Ice and Fire are the same. Like Tolkien’s Sauron, willing to slaughter however many it takes to gain power of the ring, Martin’s fantasy series is fueled by a primitive motivation: killing something to get something. And, as Martin puts it, “When you play the game of thrones, you win or you die. There is no middle ground.”

The plot in each series contains a ticking timebomb. The One Ring, Tolkien has said, is a mere mechanism that "sets the clock ticking fast”. “Winter is coming” is the line that launches the action in Martin’s universe – the promise of what will be a long frost settling over all the land.

Both authors write scenes that resemble Shakespearean history plays, interspersing swordplay with intricate dialogue, false charges of treason and beheadings. HBO’s Game of Thrones episodes have spectacular fight choreography, from flaming swordplay in the round to head-cracking and eye-gouging. Tolkien’s Gandalf, the last wizard to appear in Middle Earth, uses fire and a staff in supernatural battles. He was, Tolkien wrote, “the enemy of Sauron, opposing the fire that devours and wastes with the fire that kindles, and succours in hope and distress”. Gandalf blows whimsical smoke rings and creates breathtaking fireworks displays in the Shire. By contrast, Martin’s diversions are X-rated (brothels, threesomes, incest and gallons of sour red wine).

Both The Lord of the Rings and A Song of Ice and Fire are epic cycles: they offer plenty of escapism through dragons and direwolves, seductions and duels. Good and evil are more clearly defined in Tolkien’s vision, shaped by closeness to the two world wars of the 20th Century. Martin’s jaded view may be better suited to this era of overlapping and interlocking conflicts. And his fantasy novels also evoke more ordinary and familiar tensions, in an age when office politics and personal relationships can be vicious, even to the point of inciting revenge.

There and back again

By definition, fantasy should be a limitless genre of unbounded imagination. Isn’t it time we came up with something new?

There are two reasons for this. To start with, it’s about sequels. In the age of algorithm-assisted online shopping and ‘if you like that, you’ll like this’ recommendations, the gatekeepers at the biggest publishing companies tend to choose the tried-and-true over the quirky or original. The five novels in Martin’s series to date have topped bestseller lists and sold more than 15 million copies in all.

And secondly, the familiar prevails. Readers often gravitate toward the childhood obsessions they love, which include games like Dungeons and Dragons and books involving swordplay and witchery. And the swords-and-dragons tale works in any century, because of commonalities across Western history.

Both Tolkien and Martin relied upon Britain’s rich and brutal past, and medieval history in particular. Both drew upon cornerstones of Anglo-Saxon literature: Beowulf and Arthurian fantasy legends. Beowulf defined a heroic code of honour; the great hero fought Grendel and Grendel’s mother, and that final dragon. The Hobbit, which involves a great battle against a dragon, was published in 1937, not long after Tolkien’s Oxford lectures on Beowulf and the monsters. And for centuries, fantasy writers have drawn upon Arthurian lore arising from two 14th Century classics: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur. Tolkien and Martin’s work also connects to TH White’s The Once and Future King and Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon series, which told of Guinevere, Morgan le Fey and the great wizard Merlin. Whether mirroring, amplifying or spinning off from these earlier works, the great fantasy sagas created by Tolkien and Martin have a family resemblance because they’ve inherited the same narrative DNA.

|

Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top Top

Top